Subject matter

The field of Information literacy is very much on the move. It is important that support (advice and training courses) remains relevant to the latest developments. These are:

- international standards and developments

- contiguous or overlapping fields or disciplines

- target groups (students/teachers/researchers)

- the various disciplines of our target groups

- the professional field

- society (and societal needs)

On this page, you will find information about information literacy, metaliteracy, frameworks in which the required competencies are described, learning outcomes that form the basis for curricula, and a subject-based taxonomy that forms the foundation for sharing information literacy resources.

Information literacy and information skills are used interchangeably. Information literacy suggests that it is not just a skill that needs to be developed, but also implies an attitude or awareness in relation to information, knowing how to deal with it. Information skills refer to technical skills that have to be acquired in the fields of searching and selec ting information and processing it critically and ethically.

ting information and processing it critically and ethically.

The most commonly used definitions in higher education generally overlap and are usually formulated within a framework, which helps clarify the context of elements from a definition. (For more information, see IL Frameworks/models.)

The ACRL Framework (2015) uses the following definition:

“Information literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.”

In SCONUL Seven Pillars of Information Literacy (2011), information literacy is described thus:

“Information literate people will demonstrate an awareness of how they gather, use, manage, synthesise and create information and data in an ethical manner and will have the information skills to do so effectively.”

Information literacy is ultimately a set of competencies and attitudinal aspects that enable students, researchers, teachers, or employees in higher education to develop into lifelong researchers, learners, and critical citizens.

Metaliteracy is a renewed vision or indeed redesign of information skills. It is an umbrella term covering various literacies that have a role to play. Examples include media literacy, digital literacy, visual literacy, critical literacy and health literacy.

There is an additional focus on the creation, sharing, and distribution of original digital content in a social media environment in which you actively participate.

Metaliteracy contains an evolving set of goals/learning objectives that are related to four learning domains - metacognitive, cognitive, behavioural and affective.

The learner plays an active role based on eight characteristics: informed, collaborative, participatory, reflective, socially involved, adaptable, open, productive.

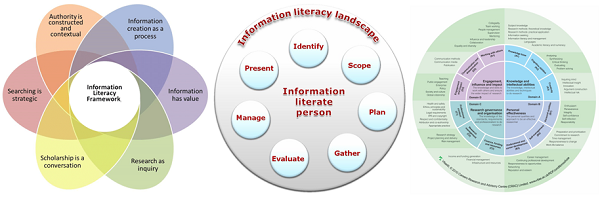

Worldwide, there are various frameworks and models that describe the information literacy competency. Each model has its own classification, sections, and approach. In many cases, there are descriptions of the required skills and behaviour, as well as of cognitive (thinking), metacognitive (thinking about thinking) and affective (feelings) aspects.

These models can be used as guides for developing lessons, for example, or for communicating with those in the education sector. They are also useful as reference frameworks to see whether your teaching is keeping up with developments. It is not just the information landscape that is changing, but also the way in which we create, consume, and share information.

Three frameworks/models commonly used in the Netherlands are the ACRL Framework, the Research Development Framework, and the SCONUL Seven Pillars. If you click on the links you will find a brief description of each of the models, as well as useful links and an overview of which institutes work with which frameworks.

More information about: ACRL Framework

More information about: SCONUL Seven Pillars

More information about: RDF Framework

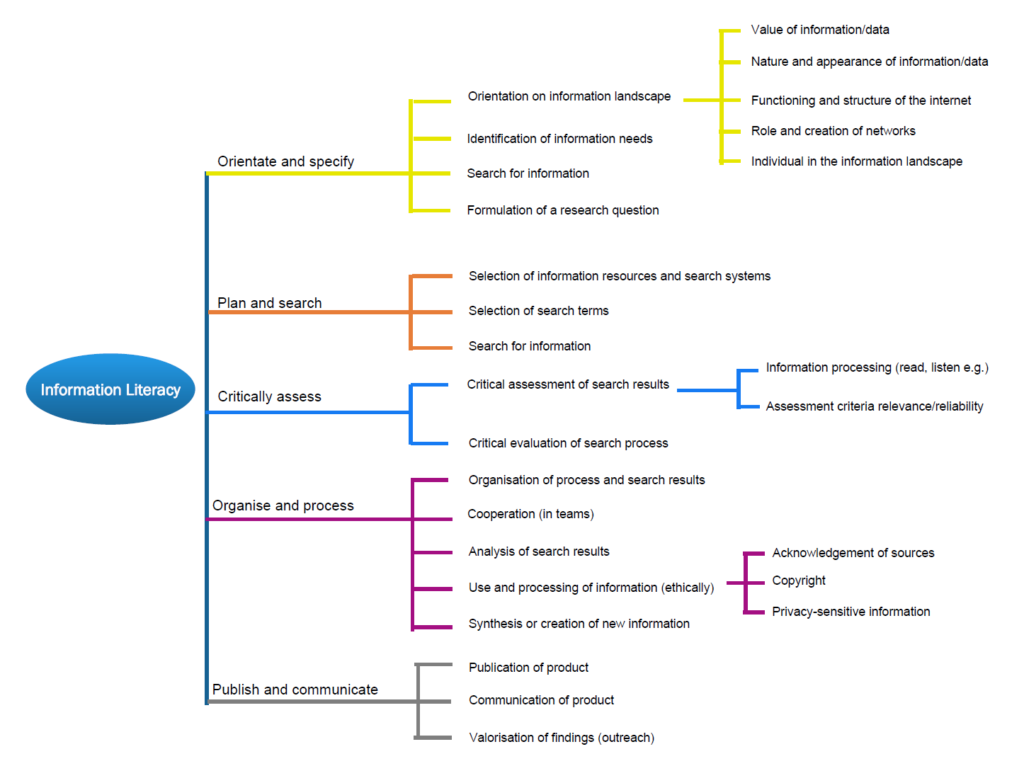

In a taxonomy, a hierarchy is used for classifying terms, subjects, or goods (Van Aalten, Van der Linden, Sieverts & Becker, 2017). Using such a taxonomy means classifying documents in a database or repository and making them easy to find.

Because the IL Working Group wished to share national teaching resources (via SURFsharekit) and because no suitable IL taxonomy was available at the time, one was created in 2020 (Van der Meer, Post, 2020). The taxonomy was based on a comparison of information literacy standards and frameworks.

More information about its creation, the comparative analysis, and the taxonomy itself can be found in Information Literacy taxonomy - comparison of frameworks.

Figure: Information Literacy taxonomy – schematically display (Van der Meer / Post, 2020)

Sources:

Aalten, J. V., Linden, M. V. D., Sieverts, E., & Becker, P. (2017). Maak het vindbaar (Doctoral dissertation, De Haagse Hogeschool)

Van der Meer, H.A.L. & Post, M. (2020). Taxonomie informatievaardigheid. Universiteit van Amsterdam / Hogeschool van Amsterdam, Wageningen University.

Digital badges are digital certificates that demonstrate that someone has certain knowledge or skills. Information Literacy is a skill for which badges can be awarded. If badges are institution-wide, it becomes easier for students to continue their studies at another programme or institution, making education more flexible. It can be efficient for institutions to participate in cross-institutional badges; once a system has been set up, other institutions can join in.

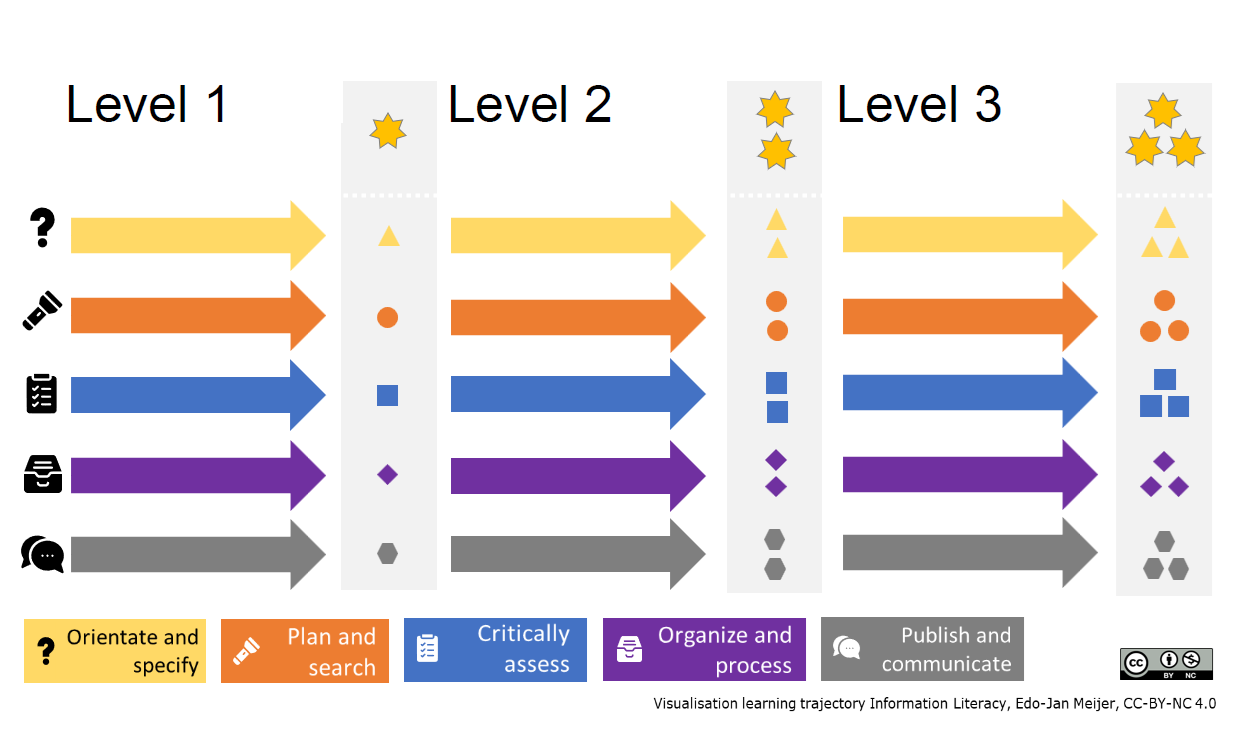

During the Project cross-institutional edubadges Information Literacy, we studied how to achieve cross-institutional edubadges. The main step is consensus on learning outcomes. As part of this, a learning outcomes matrix was developed that institutions can use to test whether their information literacy education matches the desired learning outcomes for the national edubadges.

Figure: Framework edubadges – schematic representation. Tap or move the cursor over the levels for explanation

The figure above is an adaptation of the visualization by Edo-Jan Meijer